for

Emma McKinlay

(13 May 1993 - 3 September 2017)

In September 2017, Emma McKinlay, a much-loved member of the Silent Frame editorial team, passed away at the age of 24 after a long battle with blood cancer. This page is dedicated to Emma and seeks to celebrate her creativity: as curator, designer, fashion enthusiast, painter, printmaker, wizard of words, and talented artist.

This collection of Emma's various projects is by no means complete. There is plenty that was not readily available to us at the point of its compilation, and we plan to add to it whenever we can do (possibly with your help!). We hope that it acts as a reminder of – or introduction to – just how much Emma accomplished.

Whether you are lucky enough to have known Emma, or are reading about her now for the first time, please share your responses to her art at the foot of this page. From designing student journals to writing for Vogue, from organising exhibitions to painting a sculpture that sold for thousands, there are so many of Emma's achievements to discover.

– the Silent Frame editorial team

NB: While this page is compatible with all devices, we highly recommend viewing this page on a desktop or laptop rather than a mobile phone or tablet, due to the large amount of media content and the high number of external links. Thank you for reading.

Student publications

Emma studied History of Art at the University of Oxford. During her degree, she contributed to student publications through both her writing and her design work. You can read an excerpt of an article that Emma wrote for the Edgar Wind Journal, 'Reproduction as Destruction', below.

Emma designed the layout for the Destruction issue of the journal, which you can read in full here, and designed The Sublime issue with Daniella Shreir, available to read here. She was also a member of Isis Magazine's creative team; view their Hilary Term 2013 issue here.

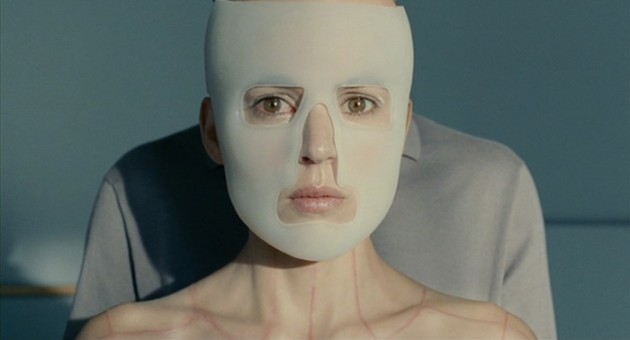

The majority of us often encounter art through the medium of photography – in books and magazines, on postcards and advertisements, as well as increasingly on the internet. Photographs of art are everywhere and yet because of this they are invisible. The photograph's ability to wrench an object from its historical context, to obliterate its tactile and three-dimensional qualities, and to fragment it beyond recognition, somehow manages to go largely unnoticed. These processes may not physically harm or alter the actual work itself, but they have a bearing upon the way in which we might subsequently approach the original, now inescapably in the light of its reproduction.

– Emma McKinlay, ‘Reproduction as destruction’

The Romance of Dereliction

In 2013, Emma was selected for the OVADA Emerging Curators Scheme, alongside two of her History of Art coursemates Hannah Clark and Rosie Turner. Together, they were invited to produce an exhibition in a disused warehouse on Osney Lane, Oxford, as part of the countywide Oxfordshire Artweeks festival. The Romance of Dereliction ran from 4-19 May 2013, and featured artworks by Aliki Braine, Zsuzsanna Nyúl, Emma Papworth, Robert Rapoport, and Mary Robinson.

The Romance of Dereliction took its aesthetic and thematic inspiration from the dilapidated state of the venue. Emma, Hannah, and Rosie's proposal describes the warehouse as both a 'blank canvas' and a 'palimpsest' – though superficially bare, the space was full of evidence of its 'patchwork history'. Drawing from the writings of the phenomenologist Gaston Bachelard, the curators viewed the 'vein-like cracks, scabbing paint, raw brickwork' as the 'lifeblood of the space'.

A small selection of photographs from The Romance of Dereliction can be found below, as well as a timelapse video of the installation and the proposal written by Emma, Hannah, and Rosie. You can find the full exhibition catalogue here. More images, all taken by Hannah Clark, are available on the OVADA/Artweeks Curator’s Blog.

The warehouse is a blank canvas in terms of the opportunity and possibility it contains, and yet also a palimpsest, its textured walls asserting a myriad of presences. The space is a paradoxical one. To us its dereliction offers up the promise of creativity. Vein-like cracks, scabbing paint, raw brickwork – these corporeal elements, the lifeblood of the space, present a fertile source of inspiration to both us as curators and to the artists we have invited to the project. The sense of patchwork history that the building evokes have encouraged responses in a variety of media, which seek to imagine its lost narratives and uncover a beauty in the dereliction. As students of History of Art we are accustomed to the ‘gallery space’, the ‘white cube’ where the environment is neutralised and devoid of character; subservient to the artwork. It is rare to find exhibition space that has not been sterilised and this exciting opportunity is one aspect that has really captured our imaginations.

– Hannah Clark, Emma McKinlay, and Rosie Turner

The Right to Flight

In July 2014, Emma volunteered with the arts organisation Bold Tendencies, as part of its Art Trainee Programme. She assisted the artist James Bridle with an ambitious artistic commission, The Right to Flight, as well as spending time caring for the Derek Jarman Garden, a permanent commission inspired by the filmmaker's garden at Dungeness.

For The Right to Flight, Emma helped fly a military-grade Helikite balloon 150 feet above the roof of Peckham multi-storey car park. Emma wrote about her (slightly nerve-racking) experience in a blog piece for Bold Tendencies. Find an excerpt below, and read the article in full by following the link here or clicking the photograph (also taken by Emma).

To fly the balloon is to taste the elation and to partake in the utopian imaginings of Nadar, the Parisian photographer and balloonist. Author of an 1866 treatise entitled 'The Right to Flight’, after which the commission is named, Nadar envisaged communication and travel via balloon bringing an end to conflict between nations. This is the intention behind James Bridle’s project: to recover the initial idealistic potential of ballooning at its inception, the technology of which has subsequently been harnessed for more sinister purposes such as surveillance. Rather than flying for the purposes of controlling people, this balloon, floating serenely over Peckham, is for people to reclaim.

– Emma McKinlay

Apollo Magazine

In September 2014, Emma interned with the international art publication Apollo Magazine. During her time there, she reviewed the exhibition Dennis Hopper: The Lost Album at the Royal Academy, London. You can read an excerpt of her piece below, and find it in full here.

Self Portrait in a Headlamp is an enigmatic photograph. It would be even more mysterious without the title, which anchors its suspended orb and spectral reflections to the concrete reality of a car’s bumper. Slightly distorted in a convex headlamp is a street scene that anticipates the subject matter of other photographs in this room; figures on a sidewalk, a road, cars, shops, signs, sky. But it is the two figures silhouetted in the foreground of this all-American tableau that command our attention. And especially the figure crouched on one knee, the man with the camera, who makes his elegant female companion linger as he captures the something that has caught his eye – their own reflections. This is Dennis Hopper, the photographer responsible for the dreamlike image itself.

– Emma McKinlay, ‘Dennis Hopper: The Lost Album at the Royal Academy, London’

Silent Frame

Emma joined Silent Frame in 2015, when the project was in its early stages. As a member of the editorial team, she played an important role in shaping the direction that the site took. The advice and guidance she gave was always thoughtful and considered, and the same can be said of her prose. Emma's articles are a joy to read, characterised by both her undeniable flair for writing and her eye for detail – she was quick to spot any clunky sentences or misplaced commas!

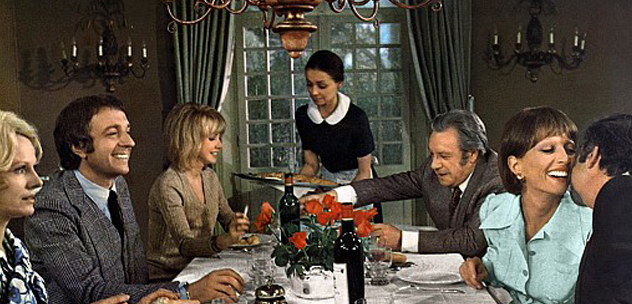

While some writers keep their subject at a distance – 'coolly recording from the passenger seat', to quote her own piece on Joan Didion's novel Play It As It Lays – Emma's pieces are warm and ever-empathetic. She had a knack for teasing out the humour and humanity to be found in even the most pofaced artworks, and her enthusiasm was by no means limited to a particular medium. She was equally confident writing on Clueless and Judy Chicago, Nora Ephron and Victor Erice.

You can read Emma's articles for Silent Frame by following the links below. Silent Frame compiles its content months in advance of publication, so further articles written by Emma will be uploaded to the site (and to this page) over the course of 2018.

Art

Driving north on the A1, gazing blankly out of the window, we are met by an arresting, celestial presence. A behemoth of steel, the Angel of the North casts a reassuringly sturdy silhouette against the changeful northern cloudscape, its colossal wings stretched out in greeting. It seems to hover over the Tyne valley, aloof and otherworldly, yet its giant, rusty feet are planted solidly on a mound in Gateshead, inviting visitors to swarm around and behold its ageing patina in friendly proximity.

– Emma McKinlay on Antony Gormley's sculpture, Angel of the North

Film

Cher Horowitz is a twentieth-century caricature, an updating of Jane Austen’s Emma for the chick-flick generation. Pampered and uninterested in high-school boys, she busies herself instead with coupling up others. Her matchmaking missions are thoughtless and frivolous, at times even manipulative, yet her intentions are good. The nineties teenager and nineteenth-century woman of leisure may seem to occupy incomparable worlds, but both affably negotiate claustrophobic societies preoccupied with status and gossip.

– Emma McKinlay on Amy Heckerling's film, Clueless

Literature

The peonies were white on the day she first arrived. They were immaculate, ornamental, and ladylike, matching the woman in the straw bonnet who placed them into her basket. Now, pushing through the loose gravel path, they have become dark red and glossy. Foreboding, ‘testing the air like snails’ eyes’, they should not be here: it is only April. Yet in front of her, there are three more. She reaches out; the petals are dry, made of cloth. The flowers burst, scattering the grey, pebbly ground.

– Emma McKinlay on Margaret Atwood's novel, Alias Grace

Vogue Talent Contest

Emma was twice a finalist in the Vogue Talent Contest, in 2016 and 2017. Her first entry, 'The Long and Short of It', is published on the Vogue website. A reflection on reluctant buzzcuts informed by her experience of undergoing chemotherapy, it is a perfect example of Emma's wise, witty prose. You can read an excerpt from the article below, and find the full piece here. You can also find links to two articles from her second entry, 'It’s a Grey Area' and 'A Dissertation on Dress' (an interview with Shahidha Bari, Lecturer at Queen Mary University of London), here and here.

Two years ago I had naturally honey-coloured hair that fell in loose waves to my waist. I considered it my best feature but it was also a warm, comforting blanket. Its unruly volume distracted attention from my shadow-ringed eyes after chains of late nights. On fragile mornings it functioned protectively, like heavy armour. And when I didn't want to shrink from the world, my hair was a way of expressing my identity. I believed it announced my carefree attitude towards grooming, summarised in the one piece of beauty advice that my grandmother gave to me: "Make the best of yourself, and then forget yourself."

I was 21 and I had just entered my final year studying art history at Oxford University when I became seriously ill with an extremely rare and life-threatening haematological disorder called Haemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (which can be sung to the tune of "Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious" or abbreviated to a more manageable HLH). After starting chemotherapy I decided to take ownership of the inevitable, shaving my hair off before it could go patchy. Beneath the unflattering fluorescent lighting in the hospital bathroom, I fought back tears as I confronted my denuded skin in the mirror; it reminded me of a plucked chicken. Having recently lost my hair for the third time, I can tell you that it gets easier. But has the current buzz over the buzzcut also helped me come to terms with it this time around? Yes, I think it might have.

– Emma McKinlay, 'The Long and Short of It'

The Guardian of the Forest

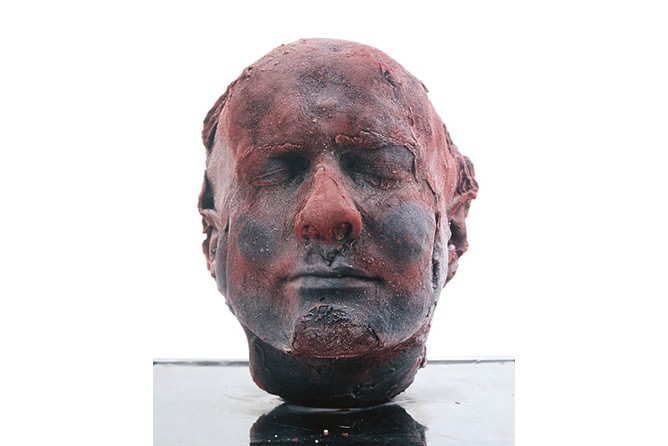

From 20 May to 3 September 2017, thirty-six sculptures of figures on horseback stood proud in Lincoln, dotted about the city as part of its Knights' Trail event. Each was displayed to mark the 800th anniversary of the Second Battle of Lincoln – in which Henry III's forces clashed with those of Louis VIII of France – and the sealing of the Charter of the Forest.

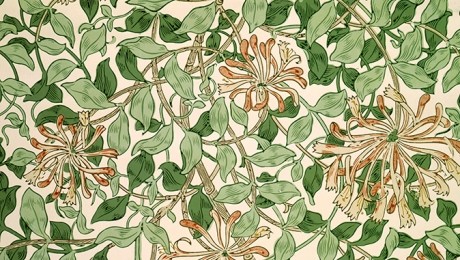

Emma was among the artists commissioned to paint a statue. Her contribution, The Guardian of the Forest, took influence from Edward Burne-Jones's tapestries and William Morris's patterned designs. You can watch an interview with Emma and read her artist's statement – complete with a characteristic pun! – below, and find out more about the event here.

Emma's knight later made a cross-country trip to London, where she was spotted outside King's Cross Station, before returning to watch over her fellow Lincolnites. On 30 September 2017, the sculpture was sold for £6,000; two thirds of the money raised from the auction was donated to the Nomad Trust, part of Lincolnshire YMCA.

The Guardian of the Forest is handsome, chivalrous and romantic. She is inspired by the virtuous knights depicted in tapestries by the artist Edward Burne-Jones, as well as the nature-inspired patterns of designer William Morris. She nobly protects the right of access to the royal forests. Like her trusty steed, she is at one with nature - a knight to remember!

– Emma McKinlay

Emma's recommendations

In line with Silent Frame's aim to celebrate the art of discovery, we have put together a virtual collection featuring some of the artworks that Emma recommended over the years. If you knew Emma and associate a particular artwork with her memory, please contact us here or mention it in a message (see the section at the foot of this page). We will then add it below. The works are divided into art, film, literature, and music; they are ordered by the artist's, or director's, surname.

NB: If an image takes your interest, clicking it will open a new tab (on an external site) with information about that artwork.

Teenage Cancer Trust

We urge you to consider making a donation to Teenage Cancer Trust, a charity that helps to ensure that young people affected by cancer receive the care that they need. Emma's family have particularly praised the support that TCT provided for Emma during her treatment. You can read more about TCT on their website here and donate via the link below.

Messages for Emma

If you have enjoyed reading about Emma's many creative projects, or if you have any memories relating to Emma's art, please do share your thoughts with us below. All messages that we receive will be published at the foot of this page.

NB: If you have any images or information relating to artworks or initiatives by Emma that have not yet been included above, please get in touch with us via our standard contact page (here) instead. Messages sent via the contact page will not be published.

We are so proud of all that Emma has done and miss her so very much. She had an eye for seeing the world around us and had words at her fingertips to inform and describe what she saw. She could create beautiful things – in her art and writings – and in her friendships with those whom she touched. Emma was a passionate believer in equality and fairness and was a kind and gentle soul. Silent Frame have produced a fitting memorial to the work she leaves behind, yet Emma had so much more to give if her life had not been cut so short. We love you Emma, thank you for enriching our lives.

– Ross McKinlay, Emma's dad

What a wide range of work Emma was involved in and I am so pleased that we had the opportunity to meet her and recognise her talent not once but twice.

– Alexandra Shulman, former Editor-in-Chief of British Vogue

Em was without a doubt the most incredible person I have ever known. I am eternally in awe of her achievements and the person that she was. The world is a colder place without her. May she forever live on in the beautiful words and pictures that she produced.

– Maddi Black, Emma's friend

Working with Emma was such a pleasure, and she wrote so beautifully about so many projects. It is a joy to look through this record of her work.

– James Bridle, fellow artist

Emma and I studied art history on the same course at university. She was the most incredibly kind and empathetic friend to me - generous, supportive and full of fun and creativity. She was a true woman of letters – often illustrated, her handwritten cards were as characteristically 'Emma' – thoughtful, wise and honest – as her articles for the likes of Vogue and Apollo Magazine.

Emma had a way of drawing together artistic influences, encountered in any number of contexts, into wildly creative, ambitious outcomes. When we read Bachelard's Poetics of Space in our first year of university, the text became a rich source of inspiration for multiple projects of Emma's, from The Romance of Dereliction to her thinking about cinematic works; her approach to spatial environments has permanently shaped my own experience of the world. When we were feeling a bit low in spirits one day at university, and decided that watching Clueless was the remedy, I had no idea that several years later Emma's thoughts on the film would come to fruition in a humorous and affectionate article, which really does do justice to its subject.

Emma was an exceptionally kind listener and confidant, and I loved that our conversations could veer from ideas about the artists we both loved - Leonora Carrington, Sonia Delaunay, Pauline Boty... – to our shared relish of clothes (especially & Other Stories) – some of my most memorable conversations about clothes have been with Emma. She wasn't afraid to tease the joy and pleasure out of all forms of creative expression and I think this comes through in the generosity and warmth of her work. I feel very privileged to have known Emma and I miss her hugely. With love xxx

– Elizabeth Brown, Emma's friend and Deputy Editor of Silent Frame

My friendship with Emma was founded upon words, both others' and her own. I was first introduced to her by members of the Silent Frame editorial team, who had studied with her at university and spoke so highly of her; any mention of her name was invariably followed by a gushing compliment or expression of admiration.

When I got to know Emma myself – primarily via email and phone calls – I soon understood why. Her warmth and wit shone through in person and on paper, and talking to her was always a joy. Her talent for writing and her love of the arts, topics on which so many of our conversations centred, were clear for all to see.

Putting together this page, though difficult, was above all a positive experience. It gave us a good excuse to revisit all of Emma's creative projects, and the opportunity to proudly share her achievements with those discovering them for the first time. We will continue to celebrate Emma and honour her memory for a long, long time to come, and we hope everyone reading this page will join us in doing so.

– John Wadsworth, Emma's friend and Editor-in-Chief of Silent Frame